Forages for Horses

This blog post is courtesy of Jennifer Earing, PhD, University of Minnesota.

Forage selection should be based on horse needs, as there is no one forage best suited for all classes of horses. For example, providing a nutrient-dense forage like vegetative alfalfa hay to ‘easy keepers’ can create obesity issues; however, that same hay would be good option for a performance horse with elevated nutrient requirements. With so many forages available, how does one choose the best option?? Differences in the nutritive quality of forages (hay or pasture) are largely based on two factors: plant maturity and species.

Maturity

Regardless of plant species, stage of maturity significantly affects forage quality.

- Young, vegetative forages are very nutrient dense and contain fewer fibrous carbohydrates (hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin).

- As the plant matures (flowers and seed heads are indicators of maturity), the proportion of fiber in the plant increases, to provide structural support as the plant gets larger. The increased level of lignin associated with maturation interferes with the digestion of cellulose and hemicellulose by hindgut microorganisms, thereby reducing the digestibility of the forage.

- More mature forages also have lower energy and protein levels than their immature counterparts.

Most horses do well on mid-maturity forages; horses with elevated nutrient requirements benefit from receiving young, less mature forages, while more mature forages are be best suited for ‘easy keepers’.

Plant species

Legumes vs. Grasses

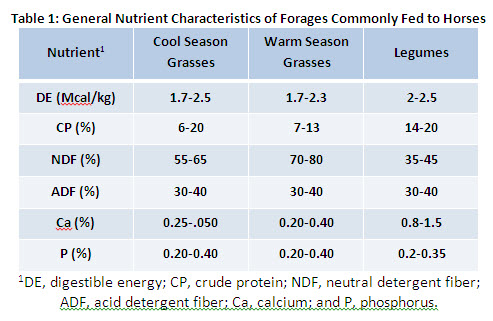

Legumes (i.e. alfalfa and clovers) generally produce higher quality forage than grasses. Often, legumes have higher energy, protein, and mineral (specifically calcium) content when compared to grasses at a similar stage of maturity, and are typically more digestible and more palatable. Legumes are an excellent source of nutrients for horses; however, a horse’s nutrient requirements can easily be exceeded when fed immature legumes. Consumption of excess nutrients, particularly energy, may result in obesity or other digestive issues. Legume-grass mixes or mid- to late-maturity legumes (which are less nutrient-dense) often provide adequate nutrients, without exceeding the horse’s requirements.

Cool Season Grasses vs. Warm Season Grasses

Cool-season grasses (CSG; i.e. timothy, bromegrass, bluegrass, and orchardgrass) typically have a higher nutritive value compared to warm season grasses (WSG; i.e. bahiagrass, bermudagrass and bluestems). At a similar stage of maturity, CSG have a higher protein content and lower fiber content. The higher fiber content in WSGs is due to the fact that they mature and become lignified more rapidly than CSGs. WSGs in late stages of maturity are typically less digestible and may be less palatable than CSGs. Consequently, if feeding WSGs it may be advantageous to harvest the forage at an earlier stage of maturity, compared to CSGs.

CSGs store the majority of their carbohydrates as fructans, while WSGs and legumes store their carbohydrates as starch. Rapid consumption of forages containing high levels of fructans, as with other water-soluble carbohydrates, may trigger laminitis in susceptible horses. Fructan levels are highest in lush spring pastures and often increase during drought conditions. Carbohydrate content of forage is an important consideration for owners of horses struggling with chronic laminitis issues, equine metabolic syndrome, and PSSM.

Differences in average nutritive values of forages commonly fed to horses are shown in Table 1.

Conclusion

The digestive system of the horse has been designed to efficiently utilize forages, and most horses can fulfill their nutrient requirements on these types of diets. Matching the nutrient levels in the forage to the nutrient requirements of the horse is one of the primary goals in forage selection. A variety of factors, including plant species and maturity, should be considered when making this decision.