Tour the Equine Digestive Tract

Ever wonder how your horse’s digestive system works? What goes on in there? Why are they so sensitive? And why should I divide the feed ration into 2 or 3 feedings per day? Let’s take a closer look to better understand.

Mouth & Teeth: Teeth are the beginning of the entire process. Designed to grind foodstuffs into smaller pieces, the act of chewing also stimulates three glands in the mouth to produce saliva. These glands can produce up to 10 gallons per day of saliva. The saliva contains bicarbonate (a natural acid buffer) and amylase (assists with carbohydrate digestion). Teeth are an important component to digestion and should be checked annually to insure proper function. A horse that is unable to effectively chew long stem forage, such as a senior horse, is at higher risk of impaction colic. If you have a horse like this, be sure to consult with your veterinarian for a comprehensive care and feeding program.

Esophagus: The purpose of the esophagus is to funnel food from the mouth to the stomach. Approximately sixty inches in length, this is a one-way passage. Unlike humans, horses cannot vomit. This is why horses who €˜bolt’ their feed (eat too fast and don’t chew adequately) can get into trouble and feeding practices need to be adjusted to reduce the risk of bolting feed.

Stomach: Small in size compared to the rest of the horse’s body, food will only spend about 15 minutes in the stomach before it moves on. The stomach is designed to function best when it is ¾ full; therefore, care takers are encouraged to provide horses with a steady supply of forage throughout the day. Because of the small size, a horse should not be fed more than 0.5% of body weight in one meal. Meals of grain are best divided into 2 or 3 portions per day.

Small Intestine: After leaving the stomach, food will spend anywhere from 30 to 60 minutes here; a good thing with the many nutrients that are absorbed. Nutrients such as proteins (amino acids), vitamins A, D, E and K, calcium, phosphorus, and other minerals along with starches and sugars. Cereal grains such as oats, barley, and corn that are high in carbohydrates (starch and sugar) are easily digested here. The horse doesn’t have a gall bladder, so bile from the liver flows directly into the small intestine to aid in the digestion of fat.

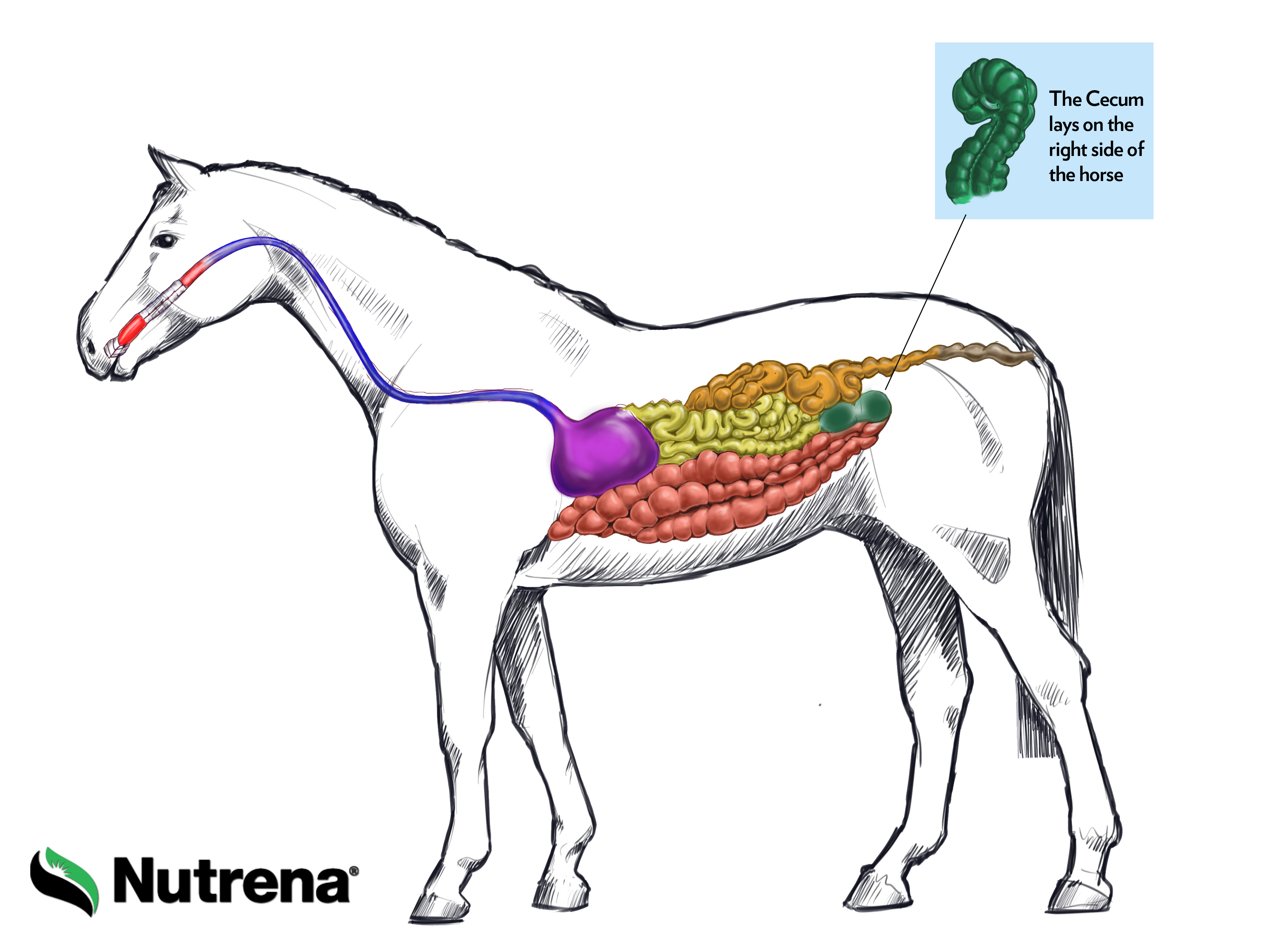

Large Intestine: is comprised of the cecum, large colon, small colon and rectum.

- The cecum is located on the right side of the horse and is where fiber is digested and converted to energy and heat. The shape of the cecum is unique because the entrance and exit are located at the top of the organ. Able to hold up to 10 gallons of food and water, the cecum contains populations of bacteria and microbes which further break down food (fiber) for digestion and absorption. These microbes are accustomed to digesting a horse’s ‘normal’ diet, so any adjustments in feed or forage should be done slowly, allowing the microbes to adjust.

- If a horse consumes too much starch in one meal, it is unlikely to be digested fully in the small intestine. It would pass through the small intestine into the cecum where the microbial organisms rapidly ferment the starch, producing excessive gas and lactic acid that could ultimately cause digestive upset or colic.

- The large colon continues the digestive process by absorbing additional fiber components and water. This is where B vitamins are absorbed.

- The small colon is where excess moisture is reclaimed to the body. This is also where the formation of fecal balls occurs.

- The rectum is where the fecal balls are expelled.

With this short tour and explanation, we hope you have a better understanding of how your horse digests and absorbs nutrients, and that this also sheds light on why good feeding management and regular dentistry care are important aspect for the digestive health and overall well-being of your horse.